Has anyone ever heard that you eat mostly organic whole foods and mocked or chided you for it because they think you're an elitist, and maybe said something like, “Too bad everyone in the world couldn't eat that way”?

Today we'll open up that discussion and see if it's really true, or if just maybe there are solutions out there that ARE working…

This post began with a Facebook question (thank you Allison): “I was wondering if you've seen this article? This woman has some good questions and is trying to resolve the conflict between living in a developing country (Tanzania) and wondering if living pesticide free, all whole foods, etc. is the way to go, and which is the best choice in her situation.”

Read the article here and the follow up here. The comments are really good, too. I debated sharing those with you, though, because they're sort of depressing and confusing, here's an excerpt:

Now, I have a pretty good way to figure out if something in Tanzania is organic. If it's got bugs in it, it's probably organic. If it doesn't, pesticides were probably involved… I can't seem to resolve this tension. I want to be into organic food, but I wonder if it's realistic. Can we really feed the world on organic food? On grass-fed, free-range meat? I read once that part of the reason organic food is so expensive is because so much of it has to be thrown away. Should we be okay with that?”

My response was that I can't help but think properly trained farmers could troubleshoot these problems with less dependence on pesticides, but since I am not even close to being a properly trained farmer (we couldn't even grow a garden because of all the deer in our yard!), I don't know the answer myself. The first thing I thought of is sending these questions to someone I know who has a masters degree in sustainable agriculture and has worked at a farm similar to Joel Salatin's Polyface, but it exists specifically to train people to teach farming in developing nations where resources (like water) are often scarce. So I asked Camille, now a farmer's market manager in Texas, to share her story.

But don't stop reading early, because after Camille's story, there is HOPE from people who are looking deeply at these issues and finding solutions!

Proverbs 13:23: “Abundant food is in the fallow ground of the poor, but it is swept away by injustice.”

Here's Camille…

In 2013, I spent a year working alongside a man from Liberia. As interns we co-managed the vegetable garden at a Central Texas training farm focused on sustainable development and faith-based mission work. After that year I went to Liberia for 3 months to work in the agriculture department of a boarding school about 15 miles outside the capital city of Monrovia. Both the internship and my college studies had been centered around the subject of sustainability in both agriculture and development. Within agriculture that meant learning about low-impact techniques, considering the environmental effects of farming practices, and trying to not only not damage the environment but enhance it through methods that could increase its fertility, like composting. Within development that meant learning to recognize power struggles – usually either governmental or corporate – and the political undercurrents flowing through issues of poverty.

Though the soil is incredibly fertile in Liberia – native “bush” plants spring up overnight and can create a vast canopy if left untended for even a season – it seemed like every other odd was against us. We grew hot peppers, cabbage, cassava, eggplant, bitter balls, sweet potato greens, corn, lettuce, watermelons, and a broad leaf green called palaver sauce which is similar to spinach, and we raised cows, sheep, goats, and pigs. The farm animals, emaciated and hungry for lack of nutrition and adequate grazing land, would break through the makeshift fencing and wipe out an entire section of 2 week-old corn plants. The grasshoppers living in the sheltered micro-climate of the surrounding “bush” would flock to the garden in droves to demolish cabbage, peppers, and bitter balls. Nearing the end of the dry season in Liberia, the wells we dug — which were simply large holes in the ground — would dry up half way through watering the crops, and we found ourselves having to dig more wells around the garden plot before we could continue with the rest of our intended plantings.

What was apparent in these situations was the lack of infrastructure or materials with which to prevent or combat crop loss: sturdier fences could have contained the animals better, pesticides could have gotten rid of the grasshoppers, more advanced equipment could have tapped deeper into the ground to ensure a more consistent water supply. What was not so apparent were the political and economic factors contributing to this oppression. Everything from seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, to equipment, repair services, and the nation’s role in the global economy were tinged with power plays that limited options and access for the people in Liberia.

There were two options for purchasing seed: either they were packaged, coated in fungicide, and shipped from Ghana with no way to tell how old they were or how long they had been exposed to the hot and humid climate of West Africa before being placed on the store shelf, or they came from other farmers in the local markets with absolutely no regulation or way to ensure their quality. Here in the States, we have a multitude of options when purchasing seed — from different seed companies, to different varieties of seed selected for different climates, disease resistance, crop yield, and storage life. These may seem like subtle factors, but the ability of one plant variety over another to withstand pest pressure or have drought tolerance can make a big impact on the success or failure of a crop.

Now some people might use this argument to promote seeds that have been genetically modified – the laboratory practice of genetically manipulating the DNA of crops by introducing genes from completely different plants — and sometimes animals — to experiment in creating new, “improved” qualities. The issues with this practice, especially in light of the developing world, are manifold. Sure, crop yield and disease resistance may be improved, and these are the surface-level, readily visible effects. What’s not so visible are the forms of disempowerment that come along with this practice of genetically modifying seeds. The companies, like Monsanto that genetically modify seeds, place patents on the specific genetic coding of the GM crops: i.e. they OWN the genetics of the seeds they sell, thereby making it illegal for farmers to save their own seed (in Monsanto’s eyes, this is stealing from them because they don’t receive money when farmers save seeds and don’t make new purchases). And in some cases, the modification of the plants includes producing barren seeds, meaning the seeds produced from that crop are infertile and will not produce another generation of crop. This creates a cycle of dependency on the GM companies and disempowers farmers by taking away a very basic form of self-sufficiency — saving their own seeds.

In their book, World Hunger: Twelve Myths, Frances Moore Lappe, Joseph Collins, and Peter Rosset, posit that “how we understand hunger determines what we think are its solutions.”

If we think of hunger as caused by failed crops or poor nutrition, our tactics for combatting it will include increasing crop yields, using any necessary means to suppress weed and bug pressure, and increasing calorie and/or nutrient counts. In and of themselves, these can be very good things. But if we can see hunger as the result of systems of oppression that create powerlessness, we can begin to tackle its root causes. We can begin to ask ourselves questions like “who controls the resources?’ and “are they accountable to the people dependent on those resources?” and “how does the government allocate its resources – does it make land use and seed or chemical regulation accessible to all its citizens fairly, or does it cater to a wealthier, elite population?” and “how many countries have export-based economies wherein foreign companies buy up land space to grow acres upon acres of a single crop (coffee, chocolate, rubber, etc) to be sold internationally on the global market, yet issues of internal food security are passed over in favor of the GNP?”

On the farm in Liberia, despite all our toil and labor, many of the crops suffered, and some members of the garden crew wanted to turn to pesticides as a remedy. “These pesticides are a product of the developed Western World, so they must be the answer to our problems,” seemed to be their general logic. On the surface, and perhaps even for a season or two, it seems like solid reasoning. Pesticides are poisons that, when applied to the plants eaten by the pests, kill the bugs and can save the crops from predation. But what about the chemicals leaching into the soil and even the waterways where the local villagers go to catch fish every day? What about the increased tolerance to chemicals each generation of pests evolves, so that more and more of the pesticides, or different, stronger ones are needed to keep maintaining the same control? Who profits from the production and sale of the pesticides, and are they held accountable in any way for the effects of the chemicals on the people and environment where they are applied?

One thing about pesticides is the mindset they create.

Jumping to the conclusion of pesticides without considering other control measures can create a cycle of dependency where ever-increasing amounts of chemicals are used to combat the pests. But who can blame someone who is dependent on their crop for their own survival? Who can blame someone who experiences hunger on a day to day basis, for turning to a method that carries promises of increasing their yield and stopping pests in their tracks?

Is hunger in the developing world caused by things like grasshoppers, or is it caused by things like the ebb and flow of trends in the global marketplace, and corrupt or negligent political figures? Will pesticides help end issues of hunger and food scarcity, or will they perpetuate systems of unequal power, dependency, and oppression? The answers, whatever they may be, are surely just as complicated as the questions.

But I do know this: in addition to learning how the people in Liberia lived their lives in community and dependence on one another for support, I also learned that grasshoppers picked off the plants early in the morning and sauteed in palm oil, made for a high-protein and nutrient-dense snack.”

Thanks Camille!

Do you want to get together with other like-minded real foodies to learn what is WORKING, and explore ways to feed the world?

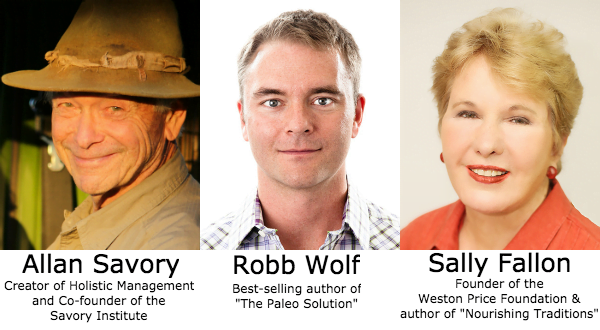

Yes, there are still struggles in finding the answers to how to feed the world real food, but there are also many successes happening, and this conference, put on by the Savory Institute (and my friend, Chris Kerston), will explore all of that — with this many great minds gathering at once, so much can happen!

Here's the link to register — or to find out more, scroll down at that same link. 🙂

Speakers will include:

- Sally Fallon Morell – Founding president of the Weston A. Price Foundation

- Allan Savory – Founder of Holistic Planned Grazing

- Anya Fernald – Co-founder and CEO of Belcampo Meat Co and regular judge on Food Network’s Iron Chef America

- Jonah Sachs – Author of “Winning the Story Wars” and co-founder of FreeRange Studios famous for their animations like “The Meatrix” and “The Story of Stuff”

- Robb Wolf – New York Times best selling author of “The Paleo Solution”

- And many, many more!

How does the Savory Institute’s work align with the real food movement?

We all know we feel better eating local, in-season, traditional foods, but what about the environmental impact of such a diet? Your friends and family might quote The China Study or Forks Over Knives when you mention your traditional diet rich in grass-fed animal protein. Questions of land degradation, climate change, methane emissions, and water quality issues invariably come up. The reality is that such data is drastically skewed by numbers that come from CAFO feedlots and are then extrapolated to be the same for grass-based livestock production when these two systems in practice couldn’t be more different.

We know that at previous points in history drastically more grazing animals existed in wild roaming herds and the planet did not suffer from the negative issues of climate malfunction and land degradation that are pinned on livestock today. This doesn’t mean that all grazing is inherently good. Livestock, like any tool, must be properly managed to achieve success.

Under the Holistic Management framework, working lands of all types dramatically improve, with increased soil organic matter, improved water holding capacity, greater productivity, and biodiversity. The holistic management movement is about real people with dirt under their fingernails and families to feed, people unified by a love of the land, a desire to understand nature’s rhythms and cycles and the magical beauty of abundant life in the soil. These are people that want security for their children, prosperous landscapes, and a life filled by a deep personal connection with nature. So don’t miss this special opportunity and come be a part of this once in a lifetime event.

At the Savory Institute’s “Artisans of the Grasslands” conference, attendees will get an in depth look at the success taking place across the globe, thought leaders will be showcased, on the ground practitioners will be celebrated, and the most up-to-date science in regards to carbon sequestration and the potential of the soil will be presented.

Attendees will leave with an understanding of how to defend their lifestyle and be plugged into a network of fellow supporters from a wide-array of disciplines. Let’s not forget that it only makes sense that human health would correlate with healthy landscapes. The healthy food and environmental restoration movements must come together to create the change needed for humans to flourish.“

Go here for more information and to get tickets.

Read more:

We all know the global issues that spell certain disaster for our species: climate change, hunger, water shortages, poverty, inequality, etc. The regenerative agriculture movement led by organizations like the Savory Institute is not based on theories proposed by think-tanks or bureaucracies, but rather solutions from innovators on the front lines who have starred these overwhelming problems in the face and found ways to overcome them.

Grasslands are some of the most important landscapes on the planet that when managed properly play a tremendous role in sequestering atmospheric carbon, increasing water quality and availability, producing healthy abundant sustainable food, and restoring biodiversity.

The Savory Institute chose to utilize their annual international conference, “Artisans of the Grasslands – Crafting the Future For Food & Agriculture”, as a forum that celebrates real world solutions to these problems. The conference is October 2-4 in San Francisco. Each speaker in their event’s line-up is a “solutionary” and has had tremendous success in their field tackling global-scale issues impacting the environment, health, economy, or humanity.

Whether you're a foodie, farmer, rancher, environmentalist, gardener, permaculturalist, new land owner, activist, investor, community organizer, or just interested in making the world a better place, the Savory Institute invites you to join the conversation. This conference will be a once in a lifetime opportunity to both learn and network.

Surround yourself with top thought-leaders from a multitude of disciplines. Engage with an international community ushering in a new era of hope. Unite with pastoralists and land managers through the universal language of the land. Come celebrate the Artisans of the Grasslands.”

Go here for more information and to get tickets to this world-changing conference!

Watch this video to understand better and for more answers:

What do you think? CAN Sustainable Farming Methods Feed the World?

More:

Camille began farming in 2009 and it has been her passion – along with local foods and sustainable development – ever since. She has traveled the States from North Carolina to Washington working on multiple small-scale organic farms through the WWOOF network (wwoofusa.org), and has completed a year-long internship with World Hunger Relief Inc., in Waco, Texas. Her education includes a B.S. in Holistic Nutrition from Clayton College of Natural Health, and studies in Sustainable Agriculture from Goddard College. She currently manages a farmers market in Central Texas.

Camille began farming in 2009 and it has been her passion – along with local foods and sustainable development – ever since. She has traveled the States from North Carolina to Washington working on multiple small-scale organic farms through the WWOOF network (wwoofusa.org), and has completed a year-long internship with World Hunger Relief Inc., in Waco, Texas. Her education includes a B.S. in Holistic Nutrition from Clayton College of Natural Health, and studies in Sustainable Agriculture from Goddard College. She currently manages a farmers market in Central Texas.

Jason M says

We need to really focus on nutrient rich soil too-it will make ALL the difference in healing people:

https://nutritionalbalancing.org/center/htma/food/articles/garden.php